By Heather King - August 2014

PAPER CITATION

Dove, T., & Byrne, J. (2013). Do zoo visitors need zoology knowledge to understand conservation messages? An exploration of the public understanding of animal biology and of the conservation of biodiversity in a zoo setting. International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication and Public Engagement. doi:10.1080/21548455.2013.822120

With over 600 million visitors each year (Zimmermann, Hatchwell, Dickie, & West, 2007), zoos play a vital role in supporting public understanding of animal biology, conservation, and biodiversity. But at what level should zoos target their educational efforts? If they pitch their explanations too low, adult audiences may feel patronized or think that the interpretation is solely for children. If they pitch too high, many visitors will not be able to engage. This study sought to examine the depth and accuracy of visitor understanding of animal biology, conservation, and the impact of humans on biodiversity.

Research Design

The study involved 100 groups of visitors to a small zoo in the south of England, with the unit of analysis being the group, rather than the individual. The rationale here is simply that most visits are undertaken in groups, and that any meaning-making will thus occur in the social context of the group’s experience. Groups comprised adults only or adults and children, with a maximum of six people.

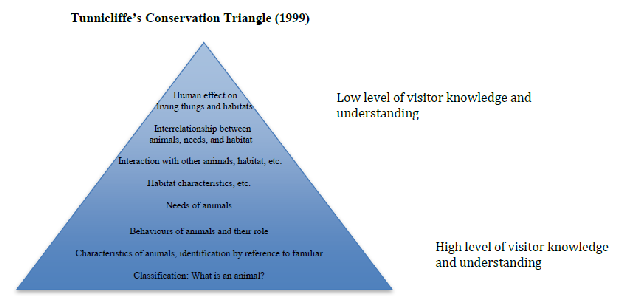

Each group completed a self-administered questionnaire as the group walked around the zoo. The questionnaire, which aimed to explore visitor understanding of eight key concepts, was constructed in the form of a challenge in order to encourage full completion and return of responses. The authors did not consider whether levels of visitor understanding were due to prior knowledge or the efficacy of zoo interpretation panels. Rather, they aimed to explore visitor knowledge and understanding of biological concepts, using Tunnicliffe’s Conservation Triangle (1999) as a reference. Tunnicliffe’s model (presented below) is based on her analysis of the spontaneous conversations of zoo visitors. At the higher levels of the triangle, visitors were less likely to understand the concept.

Each of the concepts in Tunnicliffe’s model was addressed in a specific challenge in the visitor questionnaire. For example, in order to assess visitor understanding of the interrelationships among animals, their needs, and their habitats, a food web was presented with open questions probing outcomes if one species were to disappear.

The analysis involved scoring responses against a five-level rubric and calculating the mean level of understanding per concept. Particular confusions and misconceptions were also noted, including, for example, the notion that lions roar when hungry (an aspect of animal behaviour) or that all animals need love (an aspect of needs of animals).

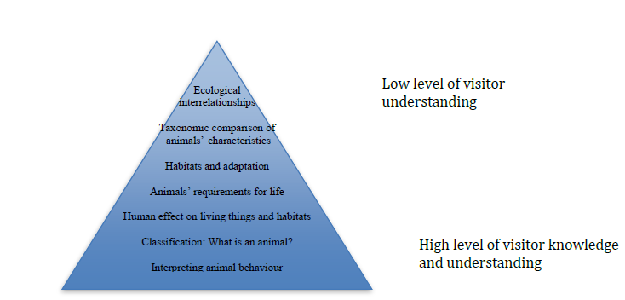

The completed analysis led the authors to amend Tunnicliffe’s hierarchy. In contrast to Tunnicliffe’s findings, this study found that zoo visitors had considerable knowledge about the effects of human activities on the natural world. However, their understanding of ecological interdependency was considerably poorer. Dove and Byrne’s new hierarchy is shown below.

The authors argue that this new model can be used by developers of zoo education programmes to identify which concepts are already fairly well understood—and could therefore be explored in greater depth—and which topics visitors find more difficult, indicating a need for more support. They note that the Tunnicliffe model was based on spontaneous conversation, so it may reflect the topics in which visitors were most interested, while this second model may offer a more accurate picture of visitor understanding. Comparing the two will remind zoo educators how difficult it can be to trigger visitors’ interest in some topics, regardless of their prior understanding.

Implications for Practice

The methodological approach here—in particular, the use of a quiz activity completed by a group— provides a useful strategy for those interested in studying learning in informal settings. Moreover, the premise underlying this study and the nature of its findings are relevant to educators in other domains. Clearly, developers must understand visitors’ prior knowledge in order to design effective experiences. As the authors note

“If visitors’ poor knowledge in [particular domains of science] means that that are unable to understand the interpretation messages, [informal institutions] must question whether that aspect of their communication mission is achievable and what they can do to make it more effective.” (page 2)

However, improvements in visitor knowledge and understanding do not necessarily lead to changes in attitudes or behaviour toward conservation. As Boyes and Stanisstreet (2012) have highlighted, the relationship between accurate understanding and subsequent action is not straightforward. More work is needed to understand how to engender visitor support and action for conservation beyond the duration of their zoo visit.

References

Boyes, E., & Stanisstreet, M. (2012). Environmental education for behaviour change: Which actions should be targeted? International Journal of Science Education, 34(10), 1591–1641.

Tunnicliffe, S. D. (1999). Zoos as centres of conservation education for primary school pupils. Proceedings of the 9th Symposium of the International Organization for Science and Technology (IOSTE) Vol. 2. (pp. 688 – 695). Durban, South Africa: University of Durban-Westville.

Zimmermann, A., Hatchwell, M., Dickie, L., & West, C. (Eds). (2007). Zoos in the 21st century: Catalysts for conservation? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.